DIY Genealogy: Saving Letters - Step 2: Scanning

Step 2: Scan Letters and Envelopes.

This post continues the Saving Letters mini-series that started with Saving Letters - Why Do It? followed by Step 1: Cataloguing. In this post, Step 2: Scanning, I set out my considerations and the method I follow for scanning my letter collection.

While I don't want to over-complicate this step, it is also not quite as simple as it might seem. Things to think about and decisions to make about the scanned files themselves include:

- Equipment and setup to perform the scans.

- Computer (or other) storage capacity for saving scanned files.

- Quality and readability of the scanned images.

- Potential obsolescence of the scanned file format(s).

- Backing up scanned images.

Working through this process gave me:

- a better comfort level that the letters would be preserved even if the originals were lost or destroyed;

- confidence that the selected file format for my letters will not become obsolete, meaning I only have to scan things once;

- I have a format of the document I can work from so that I handle the original document as little as possible, aiding preservation; and

- an increased confidence that the letters' legacy will be maintained for future generations of family historians.

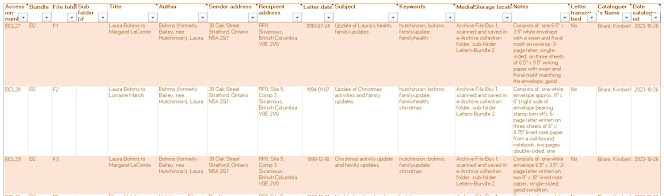

It is my hope that sharing the method I use to scan my letters will inspire you to be the archivist of your own letter collection. This second step, the scanning stage, assumes you have created a system for cataloguing your letters and that you have already logged them in your spreadsheet. If not, it's okay; but as you scan, think about how you want to use your letters (i.e., unlock the information they contain) and the details you might want to record in a spreadsheet as-you-go.

A few words about equipment.

Most people have a smartphone and one might ask the question, why not use it to "scan" my letters? Why go to the trouble and expense of researching and getting a flatbed scanner? All valid questions, the right answer will depend on finding the right balance between budget and convenenience considerations.

And there are equipment and apps to help turn your phone into a "scanner," (e.g., Google Drive, MobileScanner, or CamScanner). But for me it comes down to three things:

- getting the best image of the object I'm scanning (i.e., the contents of my large and varied family collection);

- future-proofing my file formats so that I only have to scan things once -- making it easier for those who will inherit my collection, and preserves the originals by handling them as little as possible; and

- personal preference about ensuring copyright/control/privacy of my scans.

|

| It is possible to turn your smartphone into a scanner |

Anyone who has encountered the headache of trying to get videos off of a VHS tape will understand the potential problems of format obsolescence, not the least of which is, to start, finding equipment that will play VHS tapes.

Also, sometimes the EULA terms and conditions one has to agree to in order to use some apps may mean that whatever you create using that app isn't actually yours -- the software company owns it. I am not saying this is the case with all scanning apps, but when it comes to privacy, control, and copyright ownership of my collection I am cautious. As such, I prefer to create my files offline using a flatbed scanner, store my scans on my PC hard drive, and back up my scans to a physical external hard drive.

Thoughts on file format and resolution.

Microfilm images are an archival "analog" standard for recording images. So, what is the digital equivalent -- one that will capture the properties of the original but also allow for minimal data loss when converting to other formats for more practical use? For me, that "digital master" is the .TIFF file format. The benefits of a .TIFF over another format like a .JPEG include image quality, better colour range, and is a better starting point for photoediting, and is the standard used in publishing and graphic design. The main compromise is its larger file size.

Because my goal is to start with something that preserves as much of the original image as possible, I use the .TIFF file format for my image scans. They are my "digital original" for images -- the digital master file from which I make all copies and format conversions so as to minimize data (and therefore image) degradation. Anyone who has viewed re-uploaded videos will have experienced first-hand the degradation of the image or audio that can result from too many file conversions of converted files.

But how do I treat multi-page documents? Unless I want to have a separate .TIFF file for every page, which potentially could get messy without some very precise and consistent file naming conventions, I use a different format for scanning documents like letters. While I could use a .TIFF, considering the balance of quality and convenience (i.e., in preserving the context of associated pages of a document) I prefer to use the .PDF format to create a single multi-page file for each letter.

Examples of some scans.

|

| Scan of first page of a letter |

Its main drawback is that the deck is only about 23 cm x 30 cm (9" x 12") in size but since I have a lot of photos/slides and most of my documents such as letters are this size or smaller, this scanner is my go-to piece of equipment for digitizing my family collection.

|

| Scan of both sides of the letter's envelope |

To capture all information about a letter, I scan everything, including: both sides of the envelope, the letter itself, and any other items in the envelope with the letter, such as newspaper clippings or photos.

You will notice on the front of the envelope a handwritten date. It is in my grandmother's handwriting, and it indicates the day she received the letter. And on the back of the envelope, in my great-aunt's handwriting, is the return address. Both are pieces of useful information and pinpoints their location at a point in time currently not covered by available censuses, for example.I use a resolution of 1200 dpi for my photos and 800 dpi for documents like the envelopes, letters, and newspaper clippings. This makes it easy to zoom-in on the scan in more detail than is possible with the original. And it strikes a balance between file size (the higher the dpi, the larger the file size) and quality of the scanned image or document.

These considerations also reflect a balance of equipment capability and cost. Wherever cost must take a higher priority, select the balance of scan quality and size of your collection that works best for your budget.

A word about file naming.

|

| Example of my folder- and file-naming structure |

To help locate my files, I like to organize my computer folders in a similar way to how I have set up my log of letters in my spreadsheet, and I use some elements from that log to name my file (e.g., the letter's date and the title of the letter). Similar to an index, the log makes it easy to search for, and locate, the specific file you need.

Consider disaster-proofing your collection.

Because I am investing a lot of time and effort into digitizing my collection, I back up all of my scans. I have a large collection -- including physical photographs, it is probably in the range of a few thousand items -- so I only want to do it once. This means having a back-up as a hedge against the unexpected such as fire, flooding, earthquakes or something more mundane such as a failed computer hard drive.

I have tried out using Google's MyDrive for backups, and it's definitely convenient. But subscription fees start to become a consideration once you exceed Google's free 15 GB storage limit. This may be an option for smaller collections; however, given the size of my family collection (currently over 100 GB in size), my personal preference is to back up my files to a portable external hard drive (an actual hard drive, since the failure rate of USB sticks are known to be higher, at least, anecdotally).

|

| My pocket-sized external hard drive for backups |

And as part of my disaster-recovery plan, I transcribe my letters and file both digital and physical copies in my collection "library." But more on that in future posts!

Plan to be organized.

Allot blocks of time in your weekly schedule to this process. I find a calendar on my phone to be helpful for keeping me on track. Although there is some initial time invested to set up your scanning process and schedule, once done it's easy to pick up and put down a scanning project. And it sometimes can be a welcome change of pace from a research or writing project.

Some final words.

You are investing a lot of time and effort to cataloguing and preserving your collection of letters and other objects with scans. Cost is always a consideration so invest in the best equipment that fits your budget -- there are no wrong answers! But since the reality is that you are investing substantial time and effort in preserving your collection -- and unlocking its contents by recording your collection in logs -- it only makes sense to back up your files. As they say, "an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure." Ask yourself this: Would an archivist or librarian omit backing up their files? Absolutely not. Be the archivist of your own collection; you won't regret it.

Comments

Post a Comment